Why use Rust with Python?

Python is a dynamically typed, interpreted programming language that's known for its flexibility, ease of use and low barrier to entry. It's by far the most popular language for AI, ML and data science, and has been the go-to language for researchers and innovators in these fields for quite a while now.

It's possible to write relatively high-performance code in Python these days by leveraging its rich library ecosystem (which are typically wrappers around C/C++/Cython runtimes). However, performance and concurrency are not Python's strong suits, and this requires performance-critical code to be implemented in lower-level languages. For many Python developers, using languages like C, C++ and Cython is a daunting prospect.

Rust is a statically typed, compiled programming language that's known for its relatively steep learning curve. Its design philosophy is centered around three core functions: performance, safety, and fearless concurrency. It offers a modern, high-level syntax and a rich type system that makes it possible to write code that runs really fast without the need for manual memory management, eliminating entire classes of bugs.

Although it's possible to write all sorts of complex tools and applications in Rust, it's not the best option for every situation. In cases like research and prototyping, where speed of iteration is important, Rust's strict compiler can slow down development, and Python is still the better choice.

We believe that Python 🐍 and Rust 🦀 form a near-perfect pair to address either side of the so-called "two-world problem", explained below.

The two-world problem

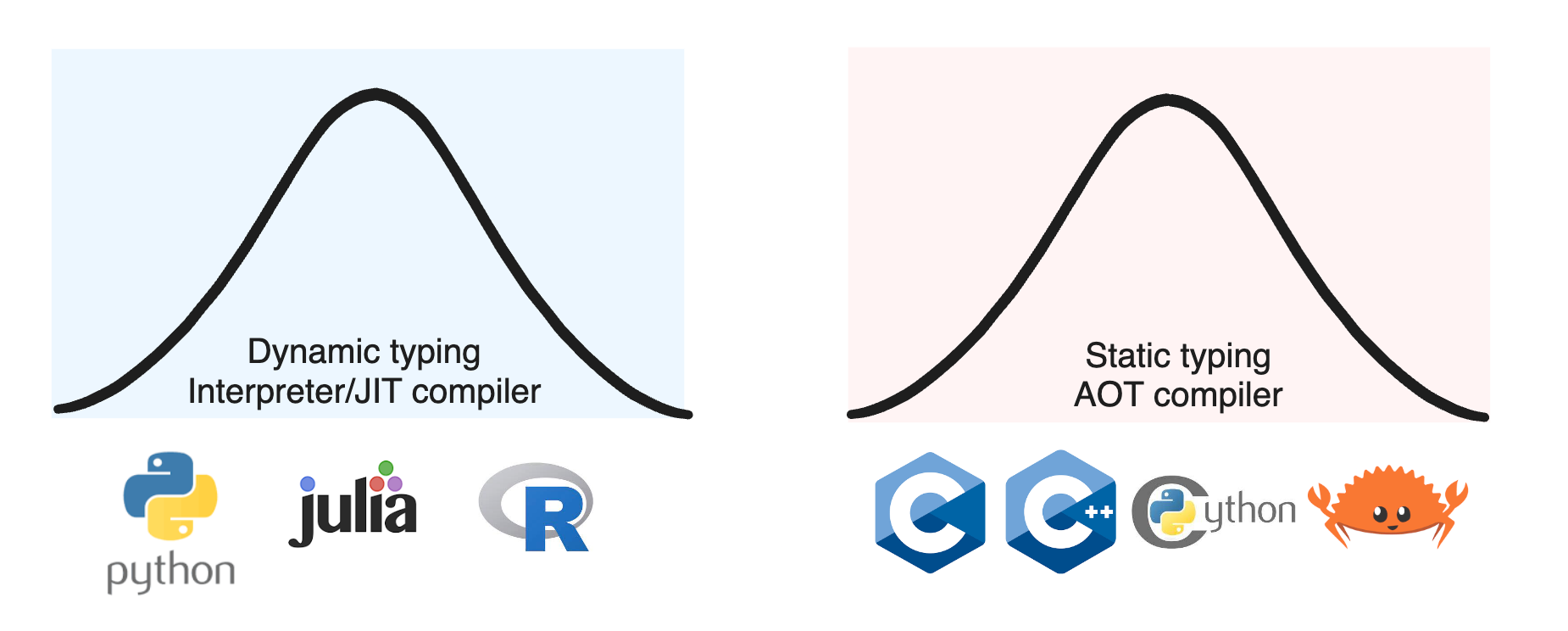

The programming world often finds itself divided in two: those who prefer high-level, dynamically typed languages, and those who prefer low-level, statically typed languages.

Many high-level languages are interpreted (i.e., they execute each line as it's read, sequentially). These languages are generally easier to learn because they abstract away the details of memory management, allowing for rapid prototyping and development.

Lower-level languages, on the other hand, tend to be ahead-of-time (AOT) compiled. They offer the programmer more control over memory management, resulting in much more performant code at the cost of a steeper learning curve.

It's for these reasons that scientists, researchers, data scientists, data analysts, quants, etc. have traditionally preferred high-level languages like Python, R and Julia. On the other hand, systems programmers, OS developers, embedded systems engineers, game developers and software engineers tend to prefer lower-level languages like C, C++ and Rust.

The image above is a figurative representation of two distributions of people, typically disparate individuals from either background (with the languages listed in no specific order).

Has the two-world problem been solved before?

A lot of readers will have heard of Julia, a dynamically typed, just-in-time (JIT) compiled alternative to Python and is often touted as a "high-level language with the performance of C". While Julia is no doubt a great language, it's popularity is largely limited to the scientific community and its library ecosystem and user community haven't yet matured to the extent that Python's has. As such, the "two-language problem" that Julia attempts to solve, is still largely unsolved.

Other languages like Mojo explain in their vision how they aim to solve the two-world problem by providing a single unified language (acting like a superset of Python) that can be compiled to run on any hardware. However, Mojo is still very much in its infancy as a language and hasn't gained widespread adoption, and its user community is non-existent.

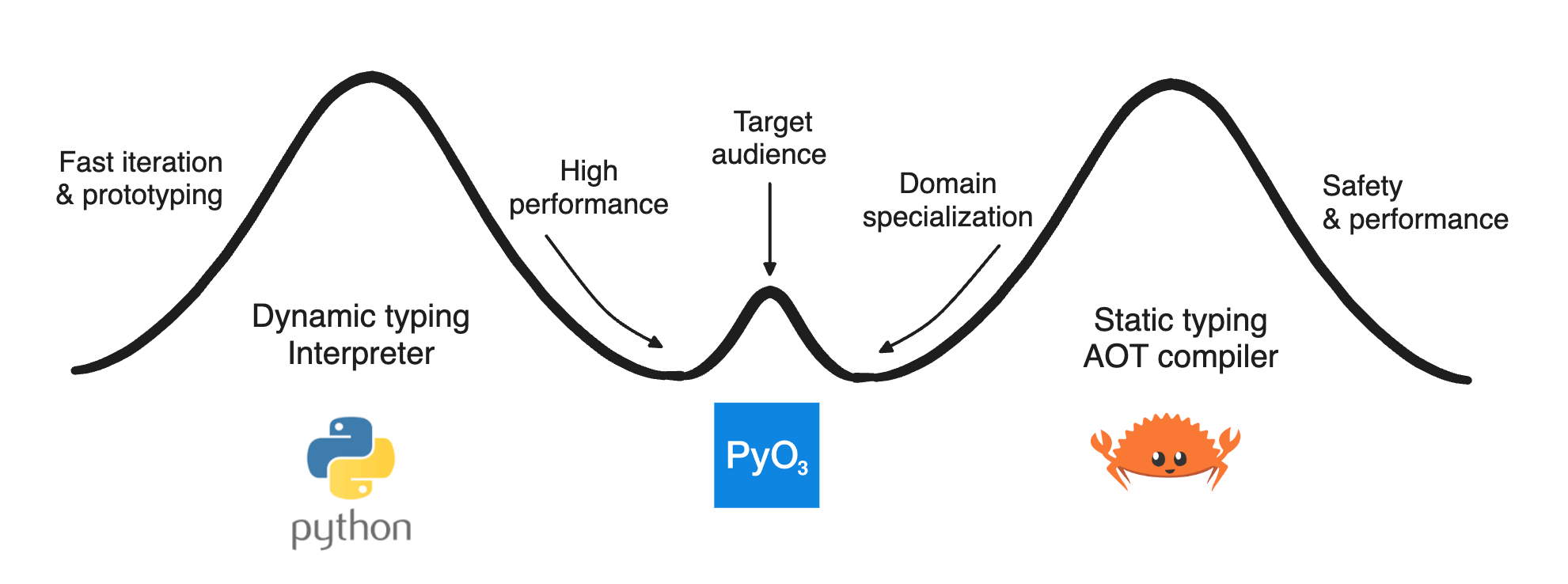

Rust and PyO3

The most interesting aspect about PyO3 in combination with Rust is that they offer a new way to think the two-world problem. Rather than trying to solve the problem by creating a new language that offers the best of many worlds, Rust and PyO3 embrace the problem by allowing a developer to move between the worlds and choose the best tool for parts of a larger task.

Rust's design philosophy and features make it an ideal candidate to bring people from these worlds (high-level and low-level languages) closer together. Rust's strict compiler, rich type system and ownership principles eliminate the need to manually manage memory without requiring a garbage collector, making it possible for a larger community of analytical and scientifically-minded developers to write high-performance code without sacrificing safety.

The image above shows a distribution of the same potential set of developers who can straddle both worlds. Those who are already proficient in Python and require fast iteration for prototyping can choose to write only very specific, performance-critical parts of their code in Rust. Conversely, those who are already proficient in Rust and require high-performance, safe code for their workflows can choose to interface with Python for only very specific parts that need access to the Python ecosystem.

In our view, the interface that PyO3 provides is fundamentally different from earlier approaches to interoperability with Python (such as pybind11, SWIG or Cython), because unlike the earlier tools, PyO3 and Rust are far more accessible to Python developers. We hope this becomes clearer and clearer as you progress through the book.